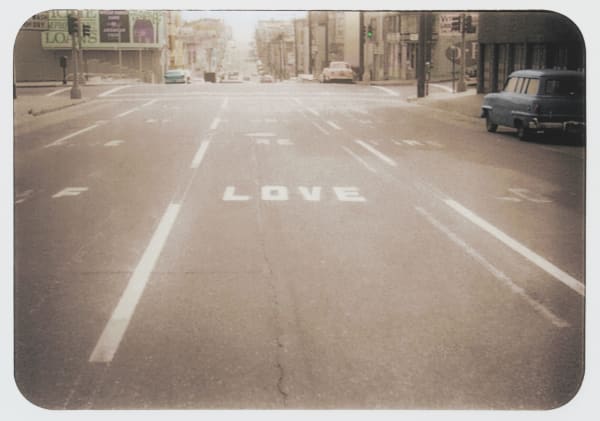

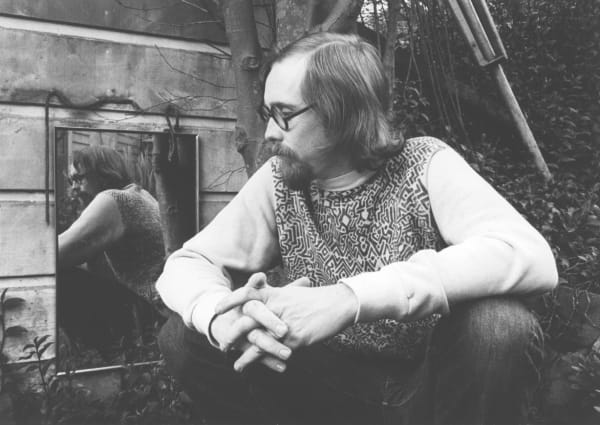

One of the most ingenious and innovative artists of the last century, Bruce Conner was a shape- shifter, refusing to be constrained to a “signature” style or single artistic persona. After receiving early critical and commercial recognition, he became increasingly disenchanted with the art world and its power to dictate the terms of artistic production and success. Over the course of six decades, he would experiment with radical inventiveness in the realms of filmmaking, photography, collage, drawing, printmaking, performance and conceptual projects, seeking in each new method the mystery in the process and the surprise of discovery, while continuously upending expectations, derailing public acclaim, and elusively evading definition or classification.

Born in 1933 in McPherson, Kansas, Conner was an iconoclast and prankster. The non-conformist ethos of San Francisco was a natural magnet, and he moved there with his new wife, the artist Jean Conner, immediately after their wedding in 1957. His sculptural assemblages incorporating nylon stockings and found objects soon attracted attention and notoriety locally, in New York, and internationally. The materials were in part born of necessity—free and ubiquitous. He and his fellow artists scavenged the detritus left in the wake of the redevelopment of San Francisco’s Western Addition, reincarnating the vestiges into artworks that questioned the values of mid-century America.

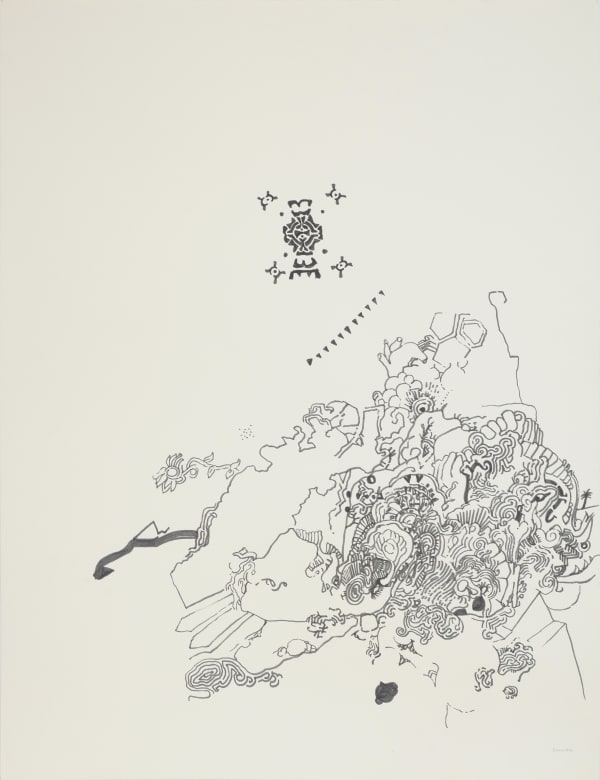

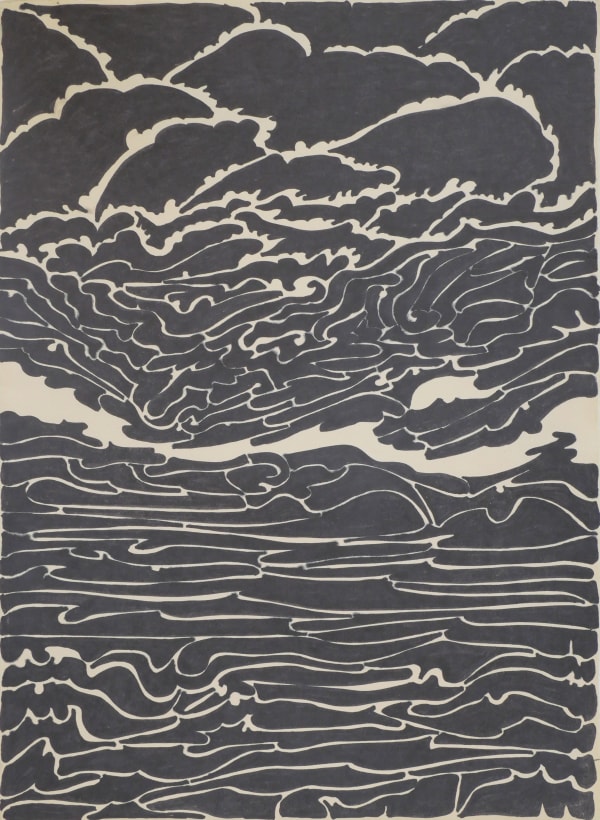

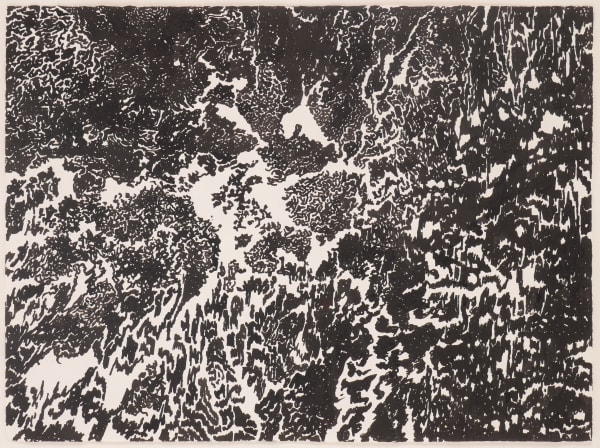

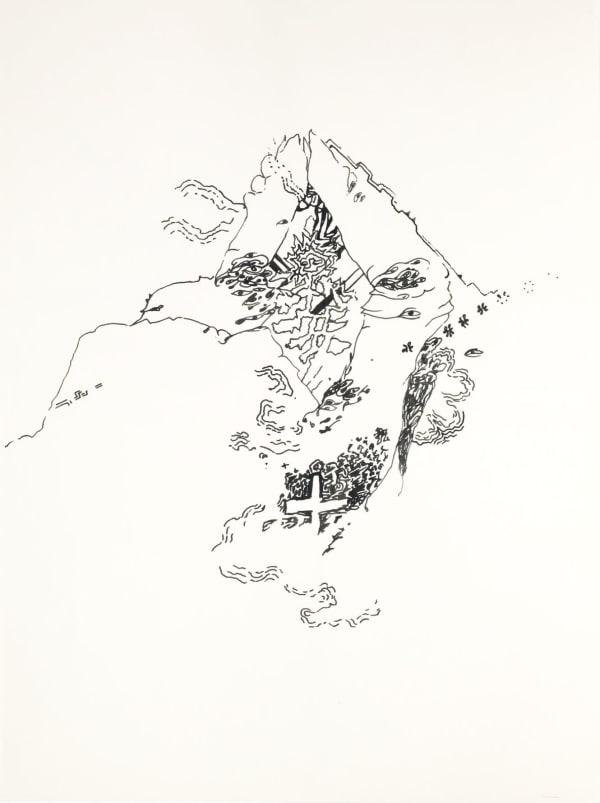

During that time in San Francisco, Conner also broadened his range of material exploration, making graphic works, film and conceptual pieces, and engaging in performance. Though drawing had always been a part of his practice, in the 1960s Conner developed technical and stylistic vocabularies which he used to create meticulously crafted works on paper that foreshadowed work he would make for the rest of his life. He gained recognition as a pioneer of experimental filmmaking, inventing a quick-cut style of editing achieved by splicing together found footage from a wide variety of sources with film he had shot. He also began experimenting in paper collage, primarily utilizing images from 19th century engravings—an inexpensive but culturally loaded source. It’s noteworthy that his films and collages—both based on the strategy of creating new meaning though unorthodox juxtapositions—were conceptually and aesthetically related to his first successes in assemblage.

But that early career recognition troubled Conner deeply – he quickly understood how it could lead to formulaic approaches and a deadening of creativity through a desire to appease galleries, critics, curators and collectors. Hence his decision in 1964 to stop making assemblage sculptures. In a 1965 letter to a friend he wrote, “I have a feeling of death from the ‘recognition’ I have been receiving… Ford Grant, shows, reviews, interviews, prizes… I feel like I am being cataloged and filed away and I have a refusal to [sic] produce something by which I will be ‘recognized.’”

Two important photographic bodies of work emerged in the 1970s. The ANGELS series, produced in collaboration with Edmund Shea, are a group of black and white photograms made through the exposure of Conner’s body and outstretched hands onto life-size photographic paper. In 1977 Conner saw Devo perform at a local club, Mabuhay Gardens, and was invited by the punk zine Search and Destroy to document the emerging punk rock scene. Conner embraced the project, likening it to “combat photography.” The resulting photographs are vivid documents of the violence, self-destruction and rebellion of that era. In the 1990s Conner revisited the excesses of this period in a group of photocopy collages memorializing punks from his Mabuhay days who had later died from drug overdoses.

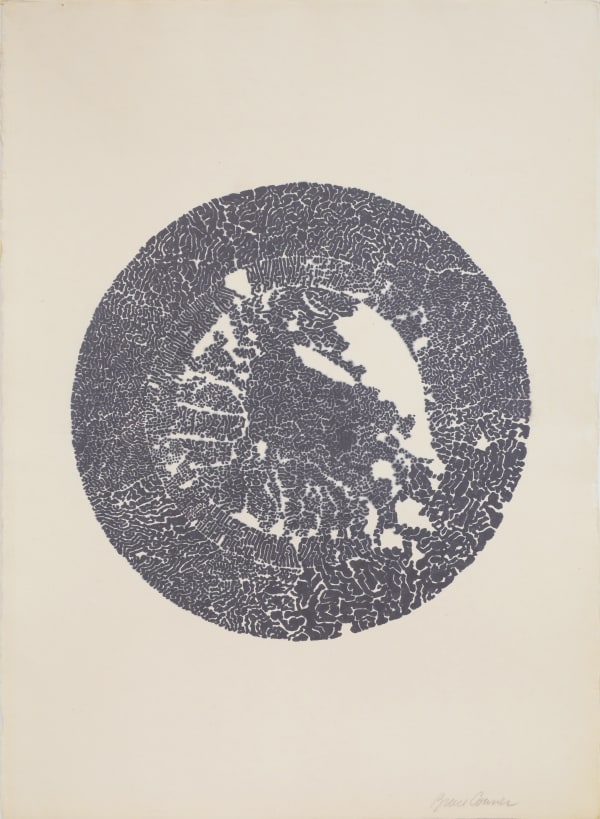

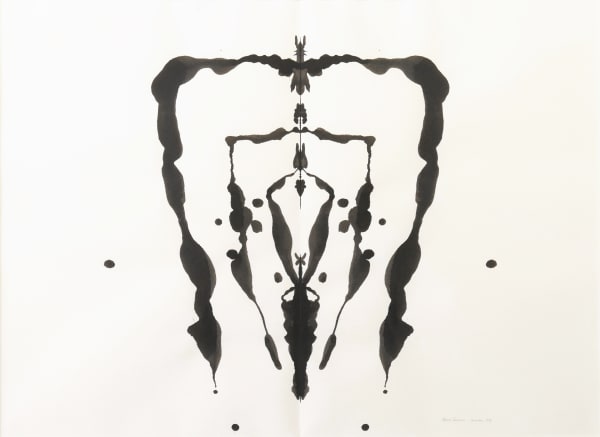

In 1975 he began his first sustained experiments with inkblots, involving repetitions of mirrored forms made from delicate, intricate lines. The technique was a perfect complement to Conner’s quest for continual reinvention and his rejection of fixed definitions—seemingly born of accident and surprise, without prejudice or intent, and fully open to the viewer’s imagination and interpretation. Conner said of the method, “The goal is to create objects that continually renew themselves, to always change, to have the potential for the process of change.”

In 1984 Conner was diagnosed with a severe congenital liver disorder that left him chronically fatigued. In the years following his diagnosis he primarily produced works on paper—mainly engraving collages and inkblot drawings. He officially announced his retirement from the art world in 1999 at the culturally prescribed age of 65. But almost immediately, Conner-like inkblot drawings began appearing under the signatures of Emily Feather, Anonymous and Anonymouse. Explaining that he had trained and paid these artists to make and exhibit artwork, Conner commended their decision to remain anonymous as it validated his goal of disrupting norms of artistic authorship and identity. Believing that a signature had become paramount to the artwork itself, at various times during his life Conner declined to sign his artworks or, instead of a traditional signature, signed them with his thumbprint or a drop of his own blood.

The refusal to be constrained by art world success allowed Conner the freedom to continually explore a range of unconventional methods and projects, making him one of the most influential artists of post-war America. His brilliance was recently and most completely explored in the retrospective exhibition and major catalogue of his work, It’s All True, organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, which premiered at the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 2016 and traveled to the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid.

-

Drawn to Drawing

12 Jul - 16 Aug 2025Todd Hosfelt combines approximately 200 drawings in an installation designed to reveal thematic and conceptual relationships across time and place. In drawings spanning the globe as well as the 16th...Read more -

Bruce Conner

Wayfinding: Bruce Conner's Marker Drawings 6 Dec 2024 - 25 Jan 2025San Francisco's Bruce Conner is one of the most important artists of the late 20th Century - pioneering art-making in sculpture, drawing, photography, collage and video. In Wayfinding , Hosfelt...Read more -

Bruce Conner + Jess

The Virtue of Uncertainty 5 Sep - 14 Oct 2023Reception: Saturday September 9, 3-5pm, with a curatorial tour at 3pm Two of the most original and broad-ranging 20th century American artists — Bruce Conner (1933-2008) and Jess (1923-2004) —...Read more -

OFF THE GRID: Post-Formal Conceptualism

11 Apr - 20 May 2023This sprawling group exhibition traces the use of the form of the grid in contemporary art, beginning with some of its most illustrious mid-20th century proponents. From there, it examines...Read more -

Where We Are

23 Oct - 24 Nov 2021In a group exhibition marking this moment in history (and celebrating the 25th anniversary of Hosfelt Gallery) the work of 34 artists is employed to reflect on the zeitgeist of...Read more -

ASSEMBLED

Bruce Conner / Jean Conner / Anonymous / Anonymouse / Emily Feather / Signed in Blood 23 Jan - 6 Mar 2021Hosfelt Gallery is thrilled to present its first exhibition in collaboration with the Conner Family Trust - a show which mines 60 years of work by Bruce Conner and Jean Conner (as...Read more -

BETWEEN THEM

An Installation Composed of Drawings 13 Jul - 17 Aug 2019Todd Hosfelt combines approximately 200 drawings in an installation designed to reveal thematic and conceptual relationships across time and place. In drawings spanning the 16th to 21st centuries, from European...Read more -

Frankenstein’s Birthday Party

23 Jun - 11 Aug 20182018 is the bicentennial of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s novel, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus . Why does a 200-year-old ghost story continue to feel so relevant? It’s important to remember...Read more -

Particle and Wave

Campbell, DeFeo, Hawkinson, Lukas, Maggi, Conner, Derges, Donovan, Ehm, Fuss, Klotz, Marioni, McCaw, Outlaw, Tomasello 6 Feb - 19 Mar 2016“Particle and Wave” is a group exhibition of sculpture, photography and technological media in which artists explore the properties of light. Reflection, refraction and color theory are used as tools...Read more -

Holding It Together: Collage, Montage, Assemblage

12 Jul - 16 Aug 2014RINA BANERJEE, JAY DEFEO, TIM HAWKINSON, EMIL LUKAS, JOHN O'REILLY, PATRICIA PICCININI, LILIANA PORTER, ALAN RATH, ANDREW SCHOULTZ, WILLIAM T. WILEY, BRUCE CONNER, JEAN CONNER, JOHN ASHBERY, JOE BRAINARD, SARAH...Read more

-

Squarecylinder on The Virtue of Uncertainty

Mark Van Proyen, Squarecylinder.com, September 21, 2023 -

The Grid Revisited

David M. Roth, Squarecylinder, May 1, 2023 -

Other Exhibits Worth Visiting: ASSEMBLED

Jonathan Curiel, SF Weekly, March 4, 2021 -

Bruce and Jean Conner @ Hosfelt

David M. Roth, Squarecylinder, February 6, 2021 -

Summer exhibition at Hosfelt Gallery a monstrous affair

Charles Desmarais, San Francisco Chronicle, July 6, 2018 -

A Celebration of the Rat Bastards: Joan Brown, Bruce Conner, Jean Conner, Jay DeFeo, George Herms, Wally Hedrick, and Ot

John Yau, Hyperallergic, May 4, 2017

-

Bruce and Jean conner at the American University Museum

February 8, 2025Follow the journey of artists Bruce Conner (iconic artist during the Beat, Psychedelic, and Punk periods) and his wife Jean (as reserved as her husband...Read more -

HG Magazine Issue no. 41

October 12, 2023In Norse mythology, Norns are three maiden giants who tend the sacred ash tree at the center of the Cosmos, nourishing it with water and...Read more -

HG Magazine Issue no. 27

Liliana Porter in the press & virtual event; plus Ben McLaughlin, Rina Banerjee, Isabella Kirkland, Patricia Piccinini, Max Gimblett, Lordy Rodriguez, Bruce & Jean Conner April 3, 2021Liliana Porter in Artforum and Artsy In Conversation: Liliana Porter & curator Humberto Moro Ben McLaughlin: Artwork Explained Art @ Home New to Inventory: Rina...Read more -

HG Magazine Issue no. 25

ASSEMBLED on view at the gallery; plus Liliana Porter, Lordy Rodriguez, Patricia Piccinini, Cornelius Völker January 31, 2021ASSEMBLED: Bruce Conner/Jean Conner/Anonymouse/Emily Feather/ Signed In Blood on view at Hosfelt Gallery Liliana Porter: Man with Axe and Other Stories opens at Frist Art...Read more -

HG Magazine Issue no. 24

ASSEMBLED: Bruce Conner / Jean Conner / Anonymous / Anonymouse / Emily Feather / Signed In Blood; plus Isabella Kirkland, Patricia Piccinini, Russell Crotty, Jutta Haeckel, Gallery Climate Coalition January 9, 2021ASSEMBLED: Bruce Conner/Jean Conner/Anonymouse/Emily Feather/Signed In Blood opens January 23, 2021 Upcoming exhibitions: Isabella Kirkland & Patricia Piccinini Art and the Environment Hosfelt Gallery joins...Read more -

HG Magazine Issue no. 18

Announcing our partnership with the Conner Family Trust September 16, 2020Hosfelt Gallery is thrilled to announce our representation of the Conner Family Trust which includes work by Anonymous, Anonymouse, Bruce Conner, Jean Conner, Emily Feather,...Read more -

HG Magazine Issue no. 17

Max Gimblett in the gallery, in the studio and at home; plus Bruce Conner & Isabella Kirkland September 3, 2020Max Gimblett: juggernaut opens at the gallery See Max at work in the studio At home with Max Gimblett & Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett New to Inventory:...Read more -

I’ll Bet Your Relationship To Art Began With A Crayon

A Gallerist's Musings July 25, 2019This installation – eighty-one artists, taken together — marks an effort to understand what “drawing” means, its emotional gravity. Cultures, continents and centuries apart… themes...Read more

-

SFARTWEEK

24 Jan 2025San Francisco Bay Area's Bruce Conner is one of the most important artists of the 20th Century - pioneering art making in sculpture, drawing, photography...Read more -

Fog Design + Art 2025

23 - 26 Jan 2025Artwork by San Francisco masters Bruce Conner, Jay DeFeo, Jess (Burgess Collins), and Wayne Thiebaud juxtaposed with works by contemporary artists Mansur Nurullah, Jutta Haeckel,...Read more -

A conversation about Bruce Conner's marker drawings

9 Jan 2025Please join us for a conversation between curator Zully Adler, Bob Conway, manager of the Conner Family Trust, and artist Lordy Rodriguez. San Francisco’s Bruce...Read more -

Dr. Devin Zuber on Jess

5 Oct 2023Join us for a conversation with Dr. Devin Zuber who will discuss his book-in-progress, Angelheaded Hipsters: Art and Esotericism in Cold War California . The...Read more -

In Conversation: Laura Hoptman and Todd Hosfelt

A virtual tour and conversation 24 Feb 2021Tune in for a virtual tour of ASSEMBLED: Bruce Conner / Jean Conner / Anonymous / Anonymouse / Emily Feather / Signed in Blood and...Read more -

In Conversation: Jodi Throckmorton and Todd Hosfelt

A Virtual Conversation Discussing the Work of Bruce and Jean Conner 5 Feb 2021Jodi Throckmorton, Curator of Contemporary Art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, in conversation with Todd Hosfelt discussing the work of Bruce and...Read more -

In Conversation: Rachel Federman and Todd Hosfelt

A Virtual Conversation On Drawing 27 Jan 2021Rachel Federman, Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Drawings at The Morgan Library and Museum, and Todd Hosfelt in a discussion focusing on the drawings...Read more

-

Fog Design + Art 2025

23 - 26 Jan 2025Artwork by San Francisco masters Bruce Conner, Jay DeFeo, Jess (Burgess Collins), and Wayne Thiebaud juxtaposed with works by contemporary artists Mansur Nurullah, Jutta Haeckel,...Read more -

FOG Design + Art 2023

19 - 22 Jan 2023An ethereal installation focusing on relationships between mid-century, Bay Area masters Jay DeFeo, Jess, Bruce Conner and Jean Conner with contemporary international artists including Jutta...Read more