Mirror Mirror

The first mirror — likely a pool of still water — allowed humans to see themselves as others did. Later came polished surfaces — copper, bronze, silver, pyrite, even stone — though the quality of the image was so very low that Paul, in Corinthians 13:12, used it as a symbol for obfuscation…seeing, as in a mirror, darkly.

As craft improved, mirrors became aestheticized — luxurious, decorative objects — costly works that denoted wealth and conferred status. Artifacts valued as much to look at as to look in.

Then came science and a myriad of uses: periscopes, telescopes and the single-lens reflex camera. Convex, fun house, side and rear view, safety, dental, architectural and one-way. Mirror image, mirror writing, mirrored sunglasses and the vanity table. The looking glass is the forerunner of the selfie. We are all Narcissus, to one degree or another.

Mirrors can represent the rational, those things we perceive through the senses; but they are also associated with the magical — windows into other realms. Ask Alice.

Vampires, we know by way of Bram Stoker and Hollywood, cast no reflection, manifesting their lack of a soul. Likewise, Dorian Grey’s portrait functioned to mirror his inner corruption. To Snow White’s wicked stepmother, the mirror did not lie, and the truth is not always pretty.

But mirrors can, and do, deceive. How many times do we need to be told that objects in the mirror may be closer than they appear? Mirrors can illustrate ambiguity, impossibility or untrustworthiness.

In paintings, photographs and film, subjects are often depicted gazing into a mirror where we, the viewer, see their reflection. These artworks are fictions. For us to see the subject’s face, the subject could not, but would instead be looking at the artist, and by extension, us.

We owe the legacy of the self-portrait to the mirror — Dürer’s, Rembrandt’s, Van Gogh’s and Kahlo’s would otherwise not be possible. In fact, a great deal of the canon of Western art relies on the representation of a mirror as its central device: Velázquez’s Las Meninas, van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait, Manet’s Bar at the Folies-Bergère, Vermeer’s The Music Lesson. Titian, Rubens, Veronese and Velázquez all painted Venus with a mirror.

Artists who use actual mirrors or reflective surfaces implicate the viewer. Our presence becomes part of the artwork. We are no longer looking at something, but become the subject of the gaze, by turns an appealing and discomforting prospect.

In art, the mirror functions as a metaphor for viewing something we otherwise cannot see… most often ourselves. It’s a mechanism by which perspective is shifted, and we gain access to knowledge that had heretofore been beyond our reach. Of course, that’s also the function of art itself. Artists hold up a looking glass within which we’re forced to confront our identity and mortality.

Artists include Jay DeFeo, Jutta Haeckel, Christian Houge, Birgit Jensen, Stefan Kürten, Michael Light, Marco Maggi, John O'Reilly, Liliana Porter, Gideon Rubin, Cornelius Völker, Monir Farmanfarmaian, Adam Fuss, Timothy Horn, Josiah McElheny, Ed Ruscha, Zhan Wang, and Carrie Mae Weems.

-

Liliana PorterBlue Eyes, 2000cibachrome print32 x 22 in

Liliana PorterBlue Eyes, 2000cibachrome print32 x 22 in

81.3 x 55.9 cm -

-

Carrie Mae WeemsNot Manet's Type, 2010digital c-print5 panels, each 40 x 20 inches

Carrie Mae WeemsNot Manet's Type, 2010digital c-print5 panels, each 40 x 20 inches -

-

-

-

Marco MaggiDrop, 2017engraved plexiglass cube, plexiglass shelf12 x 12 x 7 inches/30.5 x 30.5 x 17.8 cm

Marco MaggiDrop, 2017engraved plexiglass cube, plexiglass shelf12 x 12 x 7 inches/30.5 x 30.5 x 17.8 cm

engraved plexi cube : 4 x 4 x 4 inches/10.6 x 10.6 x 10.6 cm -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Jutta HaeckelThe Deep, 2015oil on linen39 3/8 x 31 1/2 in

Jutta HaeckelThe Deep, 2015oil on linen39 3/8 x 31 1/2 in

100 x 80 cm -

-

Stefan KürtenDeep Insight, 2016acrylic and ink on paper23 5/8 x 33 1/8 in

Stefan KürtenDeep Insight, 2016acrylic and ink on paper23 5/8 x 33 1/8 in

60 x 84.1 cm -

Jay DeFeoUntitled, 1973gelatin silver print6 1/2 x 4 3/8 in

Jay DeFeoUntitled, 1973gelatin silver print6 1/2 x 4 3/8 in

16.5 x 11.1 cm -

Stefan KürtenSilent Night, 2016acrylic and ink on paper11 3/4 x 8 1/4 in

Stefan KürtenSilent Night, 2016acrylic and ink on paper11 3/4 x 8 1/4 in

29.8 x 21 cm -

Stefan KürtenCrimson, 2016acrylic and ink on paper11 3/4 x 8 1/4 in

Stefan KürtenCrimson, 2016acrylic and ink on paper11 3/4 x 8 1/4 in

29.8 x 21 cm -

Stefan KürtenRising Tide, 2016acrylic and ink on paper11 3/4 x 8 1/4 in

Stefan KürtenRising Tide, 2016acrylic and ink on paper11 3/4 x 8 1/4 in

29.8 x 21 cm -

-

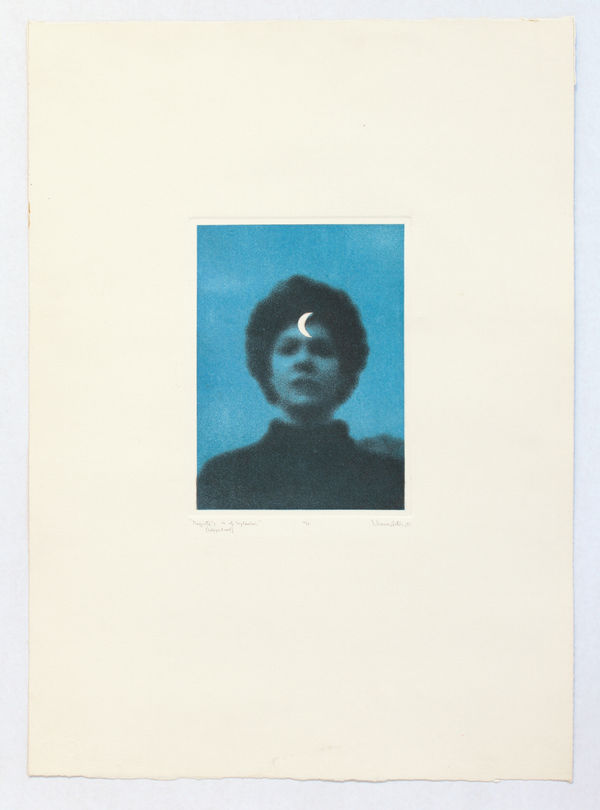

![Jay DeFeo Untitled 1973 [mirror], 1973 silver gelatin print 3 5/8 x 4 inches/9.2 x 10.2 cm, Estate no. P1118C](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7) Jay DeFeoUntitled 1973 [mirror], 1973silver gelatin print3 5/8 x 4 inches/9.2 x 10.2 cm, Estate no. P1118C

Jay DeFeoUntitled 1973 [mirror], 1973silver gelatin print3 5/8 x 4 inches/9.2 x 10.2 cm, Estate no. P1118C -

-

-

-

Cornelius VölkerPetals, 2017oil on canvas86 5/8 x 78 3/4 in

Cornelius VölkerPetals, 2017oil on canvas86 5/8 x 78 3/4 in

220 x 200 cm -

Cornelius VölkerPetals, 2017oil on canvas86 5/8 x 78 3/4 in

Cornelius VölkerPetals, 2017oil on canvas86 5/8 x 78 3/4 in

220 x 200 cm -

-

![Jay DeFeo Untitled 1973 [mirror], 1973 silver gelatin print 3 5/8 x 4 inches/9.2 x 10.2 cm, Estate no. P1118C](https://static-assets.artlogic.net/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/hosfeltgallery/images/view/bb45355273f8e40f5d13c0159a732d3118fa4ea4/hosfeltgallery-jay-defeo-untitled-1973-mirror-1973.jpg)