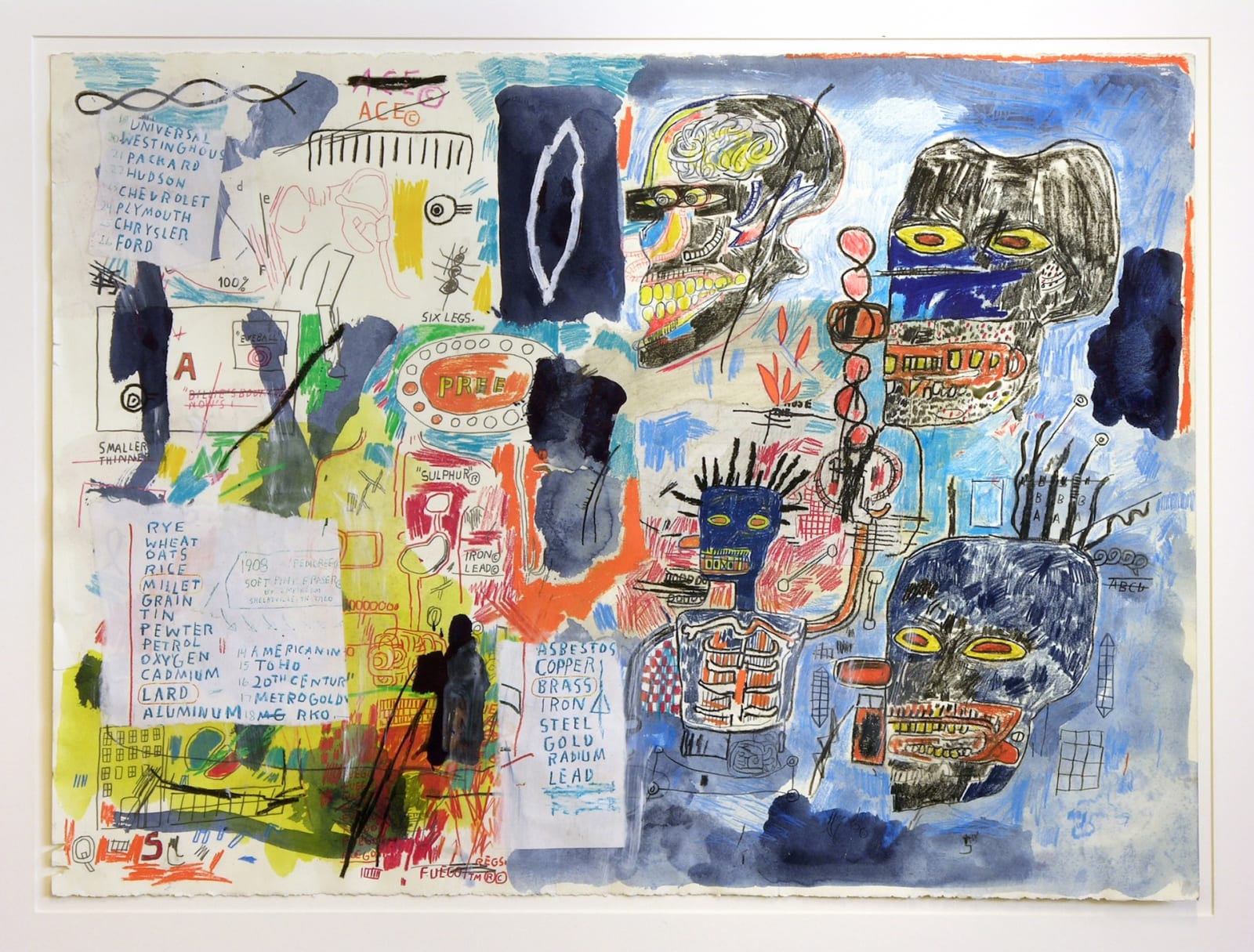

Jean-Michel Basquiat

Untitled, 1985

gouache, oil stick and watercolor on paper

22 x 30 in

55.9 x 76.2 cm

55.9 x 76.2 cm

framed

Further images

Created a year after Bushwick Avenue, this never-before-exhibited masterpiece is bursting with Basquiat’s signature imagery, text, and subject matter. Saturated with words, symbols, expressionistic gestural marks, and scribbled phrases, Basquiat’s exuberant, collage-style work incorporates references to his cultural heritage, urban upbringing, contemporary social and racial realities, and interest in human anatomy in an exploration of identity and self.

The four skeletal figures on the right illustrate a progressive deconstruction of identity. Beginning with a self-portrait with Basquiat’s distinctive dreadlocks, the artist successively breaks down this x- rayed torso and mask-like head into a disembodied masked skull, a face covered in stubble, seemly stripped of its mask, and finally, an x-ray view of the head itself. The eyes, nose, and mouth, and their connections to the brain—anatomy that allows a human to interpret and respond to stimuli in the world around him—are emphasized.

When he deconstructs this figure, we get an internal look at the basic physiology we all share—a critique of discrimination based on external appearances. It also speaks to the multi-layered nature of identity, and how the individual, society, or both, impose layers that hide who we really are. The disembodied mouth and eye are repeated motifs. The mouth representing the absence of the African American voice in society, and the eye the way we judge (or pre-judge) others.

Typically, Basquiat’s self-portrait is an heroic figure—with arm raised in the triumphant pose of a conquering warrior. Instead of wielding a sword, he holds what appear to be repeated symbols of eternity, speaking to the artist’s obsession with fame and associated need to secure his place within the history of art—ensuring his immortality. The name of famous jazz musician Charlie Parker’s daughter, “Pree,” is used to reference another black American symbol of success. For Basquiat, Charlie Parker was a contemporary hero—a musical genius who stood as an example of how African Americans could excel and achieve fame. Yet it’s also likely that Parker served as a cautionary tale for the artist, as his failure to copyright his compositions allowed him to be taken advantage of by the predominately white music industry. Consequently, Basquiat’s abundant use of the copyright and trademark symbols—which date back to his beginnings as SAMO—can be viewed as both an allusion to Parker, and representative of the need to protect against society’s corruption and callous exploitation of African Americans.

Reminiscent of the textual works of Cy Twombly, Basquiat’s lists are also common motifs in his work. In this piece, Basquiat combines lists of agricultural and mineral commodities, movie studios, and types of cars—the raw materials and products of capitalism. Base metals are common in Basquiat’s lists of commodities: references to alchemy and the pseudo-science of turning dross into gold; an

allusion to his own ability to borrow from what were considered more base forms of art—graffiti, punk, the naïf—and transform them into commercially successful works. By combining commodities of widely ranging values within a grocery list format, Basquiat comments on the substantial socio- economic gaps that exist in close proximity in America. However, these lists can also be viewed as the artist’s way of creating some order in his world, making sense of it.

This work also alludes to Basquiat’s roots. The postcard refers to the period of time when Basquiat was first starting out as an artist after dropping out of high school, and would support himself by making and selling postcards. The grids within this work often refer to “skelly-court,” a street game Basquiat may have played as a child, or was familiar with from his days as a graffiti artist.

Fluent in Spanish, the word “fuego” seems to assume special significance in this work. Repeated lower left in red ascending columns, it is not hard to imagine these words as the flames they signify, consuming a smoky black mass resembling a human figure—potentially a commentary on America’s history of racial persecution and demonization. The repetition of the word can also be seen as a reference to the rhythm and beat of jazz, as well as the fire of artistic inspiration, or Basquiat’s anger at society and its innumerable injustices.

Basquiat equates text and imagery in a manner similar to Ed Ruscha and William T. Wiley. He uses language to create rich imagery and evoke cultural references, as well as to deny meaning through linguistic redundancy (for example, by repeating the copyright or trademark symbols they become meaningless in their excess). We also see him employing the technique of erasure in order to call attention to what has been edited, by literally crossing out or attempting to erase text.

The erasures also subvert the idea of the “finished” artwork. Part of the perpetual allure of Basquiat’s work is the ambiguity in his symbolism that allows for the possibility of multiple, disparate, and even conflicting “meanings.” Perhaps this was Basquiat’s lasting challenge to the established social, cultural, and art historical hierarchies; a commentary on the complexity of identity and the absence of easy answers.

SOLD

Exhibitions

Dallas Museum of Art, "Dallas Collects Jean-Michel Basquiat" January 31 - March 28, 1993. Curated by Annegreth Nill.