Isabella Kirkland American, b. 1954

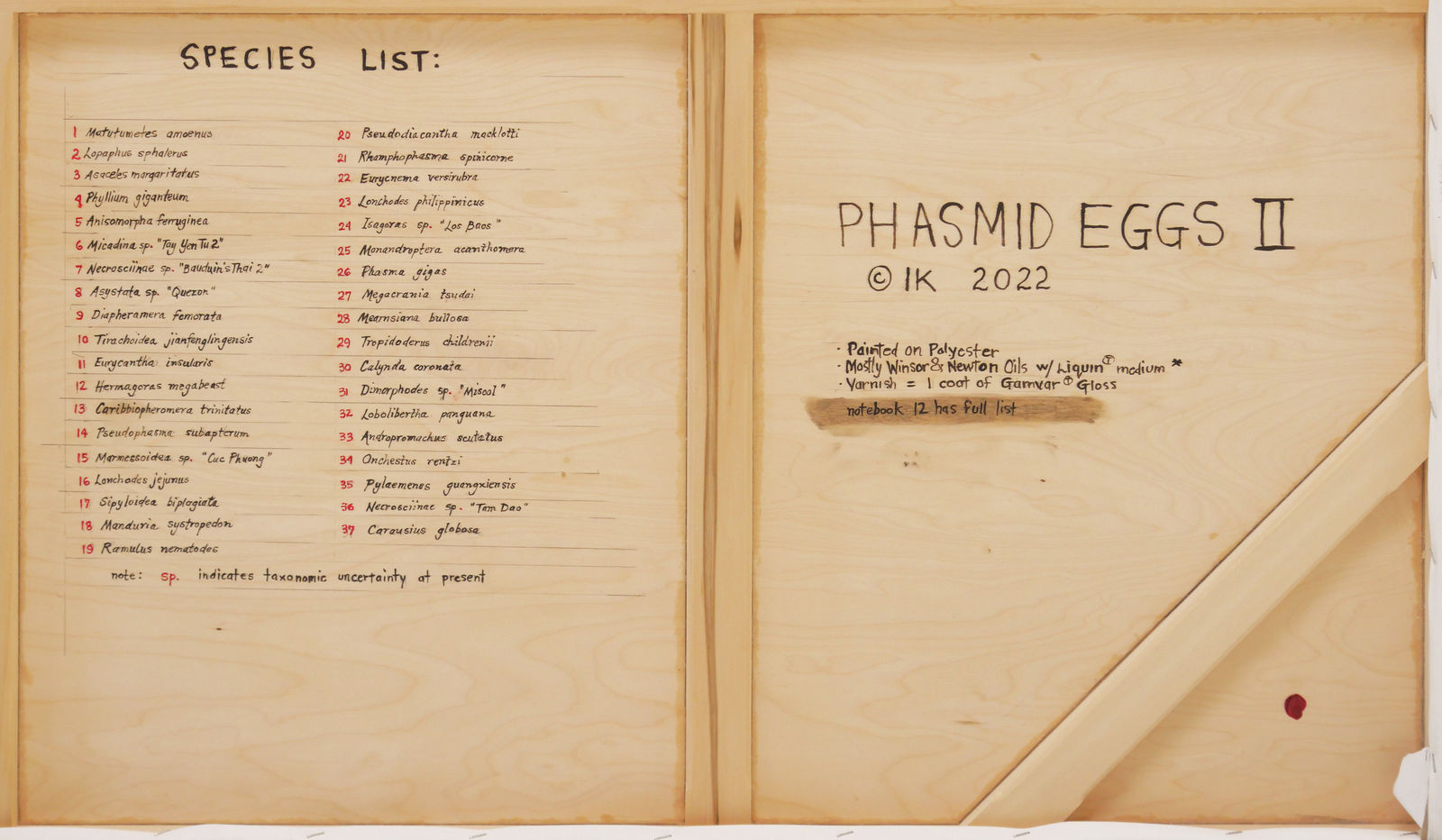

Phasmid Eggs II, 2022

oil on polyester over wood panel

48 x 60 in

121.9 x 152.4 cm

121.9 x 152.4 cm

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 12

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 13

)

Phasmids, commonly called stick insects, are herbivorous insects that uncannily resemble twigs or dead leaves. They range in size from tiny half-inch splinters to mighty half-meter walking tree branches, using...

Phasmids, commonly called stick insects, are herbivorous insects that uncannily resemble twigs or dead leaves. They range in size from tiny half-inch splinters to mighty half-meter walking tree branches, using their amazing camouflage to hide from predators and stalk their insect prey. But phasmids have one more trick up their sleeve.

Biologists L. Hughes and M. Westbory, writing in Functional Ecology, describe the amazing, or rather amazingly unremarkable, appearance of stick insect eggs. They vary by species, but some phasmid eggs look exactly like seeds. This poses a conundrum: why would an animal that looks so inconspicuous have eggs that resemble a tasty snack?

As Hughes and Westbory explain, for stick insects that leave their eggs on the leaf litter, the eggs are intentionally attractive. Eggs of these species have an unusual structure called a capitula, a lumpy appendage stuck to the end of the egg. Its function was a mystery until Hughes and Westbory compared the eggs to actual seeds, some of which have their own appendage called an elaiosome.

The elaiosome is filled with fat, with one main purpose: to attract ants. The ants take the seeds with elaiosomes back to their nests and bury them. Fooled by the capitula, they do the same with phasmid eggs. The buried eggs gain protection from parasitic wasps. Baby stick bugs then hatch safely beneath a couple centimeters of soil. The whole system is a great example of convergent evolution, when two completely unrelated organisms, an insect and a plant, independently evolve similar adaptations.

From "The Incredible Phasmid Egg" by James MacDonald

https://daily.jstor.org/the-incredible-edible-phasmid-egg/

Biologists L. Hughes and M. Westbory, writing in Functional Ecology, describe the amazing, or rather amazingly unremarkable, appearance of stick insect eggs. They vary by species, but some phasmid eggs look exactly like seeds. This poses a conundrum: why would an animal that looks so inconspicuous have eggs that resemble a tasty snack?

As Hughes and Westbory explain, for stick insects that leave their eggs on the leaf litter, the eggs are intentionally attractive. Eggs of these species have an unusual structure called a capitula, a lumpy appendage stuck to the end of the egg. Its function was a mystery until Hughes and Westbory compared the eggs to actual seeds, some of which have their own appendage called an elaiosome.

The elaiosome is filled with fat, with one main purpose: to attract ants. The ants take the seeds with elaiosomes back to their nests and bury them. Fooled by the capitula, they do the same with phasmid eggs. The buried eggs gain protection from parasitic wasps. Baby stick bugs then hatch safely beneath a couple centimeters of soil. The whole system is a great example of convergent evolution, when two completely unrelated organisms, an insect and a plant, independently evolve similar adaptations.

From "The Incredible Phasmid Egg" by James MacDonald

https://daily.jstor.org/the-incredible-edible-phasmid-egg/